Globally, there are over 1 billion people[i] with a disability. Despite this fact, this is a demographic that is largely forgotten, particularly when it comes to how they purchase and consume everyday products.

Indeed, according to research from the Royal National Institute of Blind People (RNIB), four in ten[ii] visually impaired people feel cut off from things and people around them. Inaccessible information and digital exclusion are contributing factors to feelings of isolation.

With less than 10% of organisations having a targeted plan to access the disability market, this is a huge source of frustration for disabled people, but also a huge missed opportunity for manufacturers and suppliers.

It should not, and does not, have to be this way. A big part of brand promise should be inclusivity, and while great strides have been made in recent years, technology has historically been a limiting factor in supporting that drive. However, we are now seeing innovation and collaboration helping to overcome these challenges.

From enhancing the in-store shopping experience to improving day-to-day usability, technology exists which can make product packaging and labelling more accessible and inclusive, as Nitin Mistry, Global Account Manager, Domino Printing Sciences (Domino), explores.

Consideration over compliance

People with disabilities are the world’s largest minority, as recognised by the World Health Organization (WHO). And yet, when it comes to regulatory standards around obtaining information, this is a part of the consumer base that is poorly represented. If we consider food packaging, for example, the Food Standards Agency stipulates certain mandatory information and a minimum font size for that information; yet these standards are hardly accessible for those with limited or failing eyesight, and entirely meaningless for those with no sight.

In this example, basic compliance with the standard doesn’t reflect real customer value or demonstrate a brand’s social responsibilities. The answer is to treat all customers with consideration. Fortunately, an increasing number of brands are recognising this need for greater inclusivity. Forward-thinking manufacturers and suppliers are working with disability groups, technology suppliers and, indeed, investing in internal staff initiatives to help them understand the needs of those people with disabilities. They are exploring and identifying ways to make products more accessible, particularly where packaging similarity might cause confusion and even risk.

Understanding the context

When making products more accessible and inclusive, a large challenge for brands lies in understanding the context in which they are being used. For example, the shopping experience presents an entirely different set of challenges to the day-to-day use of most products.

Information that is important for the ‘weekly shop’ – e.g. nutritional information, allergens, best before dates – has to be conveyed in a way that can be easily accessed both online and in-store; and in such a way that people with disabilities do not have to be reliant on either store assistants or carers to help them. In many cases, this is easier to achieve online than it is in-store, but brands and retailers are exploring how technology can support the physical shopping experience through the application of mobile applications with audio readers, or QR codes linked to audio descriptions, amongst others.

However, these applications are of significantly less value when it comes to every-day use of a product. It’s inconvenient to have to scan cupboard food packaging with a phone to differentiate mayonnaise from ketchup, for example, or plain flour from self-raising. It’s impractical to use the same method to distinguish shampoo from conditioner in the shower.

Having to place an elastic band around night cream to differentiate it from day cream – a strategy often used by blind or partially sighted individuals to help distinguish between similar products – is not just annoying; it is time-consuming, can be prone to error, adds to feelings of isolation, and is completely sub-optimal from a brand experience.

So how can brands make their products more accessible?

Inclusivity in labelling

There are a number of great examples of organisations leading the way in this field. Amongst the forerunners is Procter and Gamble, under the guidance of their Company Accessibility Leader, Sumaira Latif – who is also the company’s first blind, British Asian woman to be appointed Associate Director.

Since Sam’s appointment, P&G has launched products such as its ClearBlue pregnancy test kit on the ‘Be My Eyes’ platform, so low vision consumers can video call for pregnancy test readings. It has added Audio Description to all TV advertising. And, significantly, it now runs disability challenges with senior leaders and staff, helping them to ‘walk in the shoes’ of a consumer with a disability, which, she says, “brings to life the impact that small changes can make. Making our products more accessible adds meaning to our products and services, and makes staff more passionate, engaged and driven to a more successful outcome.”

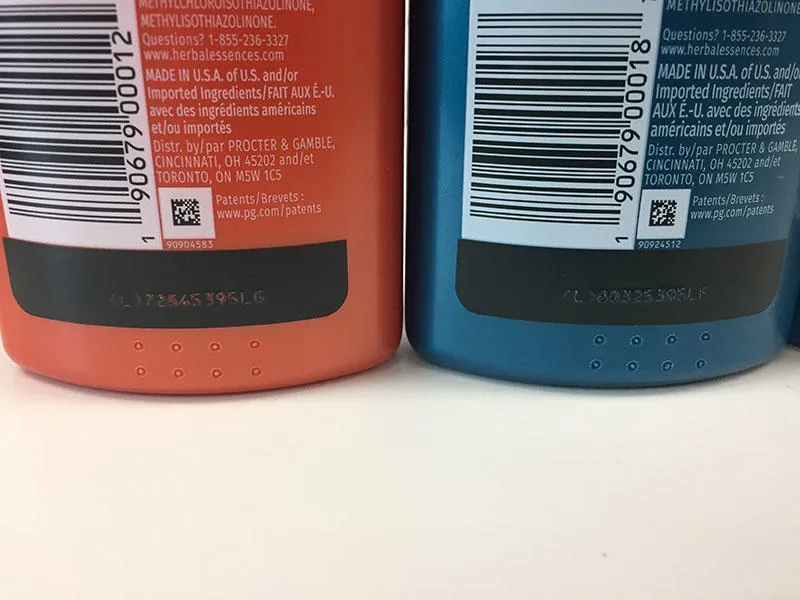

Working with Domino’s coding and marking team, P&G has also implemented tactile markers on its Herbal Essences bio:renew range of shampoo and conditioners. The tactile markers, which are added to the bottles after blow moulding using a CO2 laser, have been introduced to help visually-impaired users distinguish between the products during use. The simple addition helps to make the every-day experience easier – as Sam puts it, no one wants to rely on someone helping them to find the right bottle, especially somewhere as private as the shower.

The potential for tactile markers as an inclusive solution for blind or visually impaired consumers is significant – not only could such a solution be used to help distinguish between products, but it could also be used to indicate the presence of a 2D code to provide additional information, or further support the in-store shopping experience.

Moreover, inclusivity is not just about disabled people. Tactile solutions can also be applied to make certain products more usable for the elderly or less-able consumer, for example, a laser coder could be used to create etching to give peel-able packaging more grip for those whose grip strength may have declined. Similarly, visual tactile markings and symbology can be used to help consumers without native language capability to still understand key pieces of information, such as a moon printed on night cream packaging, versus a sun on day moisturiser.

All these examples are important in helping those with disadvantages – whatever those may be – to be independent.

Conclusion

Inclusivity has never been more important. The industry has more than just a social and moral obligation to make products more accessible. It’s the right thing to do. In equal measure, though, brands cannot ignore the commercial opportunity of reaching a broader market and engendering customer loyalty amongst a consumer audience that has historically felt neglected and frustrated.

Brands can work with their providers to think outside the box and find a solution that works for them. Coding and marking partners can offer different solutions, whether it’s printing QR and Data Matrix codes or creating tactile packaging with laser coding solutions and textured labels, which can work as stand-alone solutions or in conjunction with each other.

The technology now exists for information to become more accessible, only the determination to make it so is needed. Afterall, the benefits are manifold. As Sam says: “It’s a win for disabled consumers who often have been forgotten about. A win for business as by making products more accessible, you increase the number of people who can use and buy your products. And a win for your organisation, as employees love working when it is more meaningful, and they can see the real impact it has on individuals.”

[i] United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, “Factsheet on Persons with Disabilities”, accessed 7th June 2021. https://www.un.org/development/desa/disabilities/resources/factsheet-on-persons-with-disabilities.html

[ii] RNIB, ‘My Voice’, accessed 7th June 2021. https://www.rnib.org.uk/knowledge-and-research-hub-research-reports-general-research/my-voice